Statue wars

Hello! This week our top story is the aborted attempt to return a statue of a notorious Soviet spy chief to downtown Moscow. We also look at the discount store chain heading for a record IPO, and have highlights from the first article in our new series on how Russian money finds its way to Europe.

Abrupt end to debate over iconic spy chief statue

The Russian authorities this week sent the question of re-installing a statue to Soviet secret police founder Felix Dzerzhinsky to the top of the news agenda. The toppling of Dzerzhinsky in 1991 from his podium outside the then-KGB headquarters in downtown Moscow was a symbolic turning point for Soviet power, and its return is a deeply divisive issue. So, when Moscow City Hall put ‘bringing back Iron Felix’ to an online poll and then cancelled the result at the last minute, it caused much head-scratching. Some suspected the Kremlin was engineering a distraction in the wake of the jailing of opposition leader Alexei Navalny, but the saga could equally have been part of a struggle between warring Kremlin factions.

- An open letter calling for the return of the Dzerzhinsky statue was published on Feb. 8, just a few days after Navalny received his prison term. It was the work of several prominent Russian ‘alt-right’ figures, led by writer Zakhar Prilepin, who fought in Eastern Ukraine. Nobody doubted the letter had Kremlin approval.

- Dzerzhinsky was the founder of the All-Russian Extraordinary Committee (Cheka) in 1918. Later, this organization became the KGB and, today, it is known as the Federal Security Service (FSB). Dzerzhinsky did not live to see Stalin’s purges, which meant the post-war Soviet authorities could cast him as a “true, honest and incorruptible security officer” and his statue was installed in front of the KGB headquarters in 1958 during Khrushchev’s de-Stalinization program. However, Dzerzhinsky was more than familiar with purges and summary executions: under his leadership, the Cheka gained a fearsome reputation for brutality.

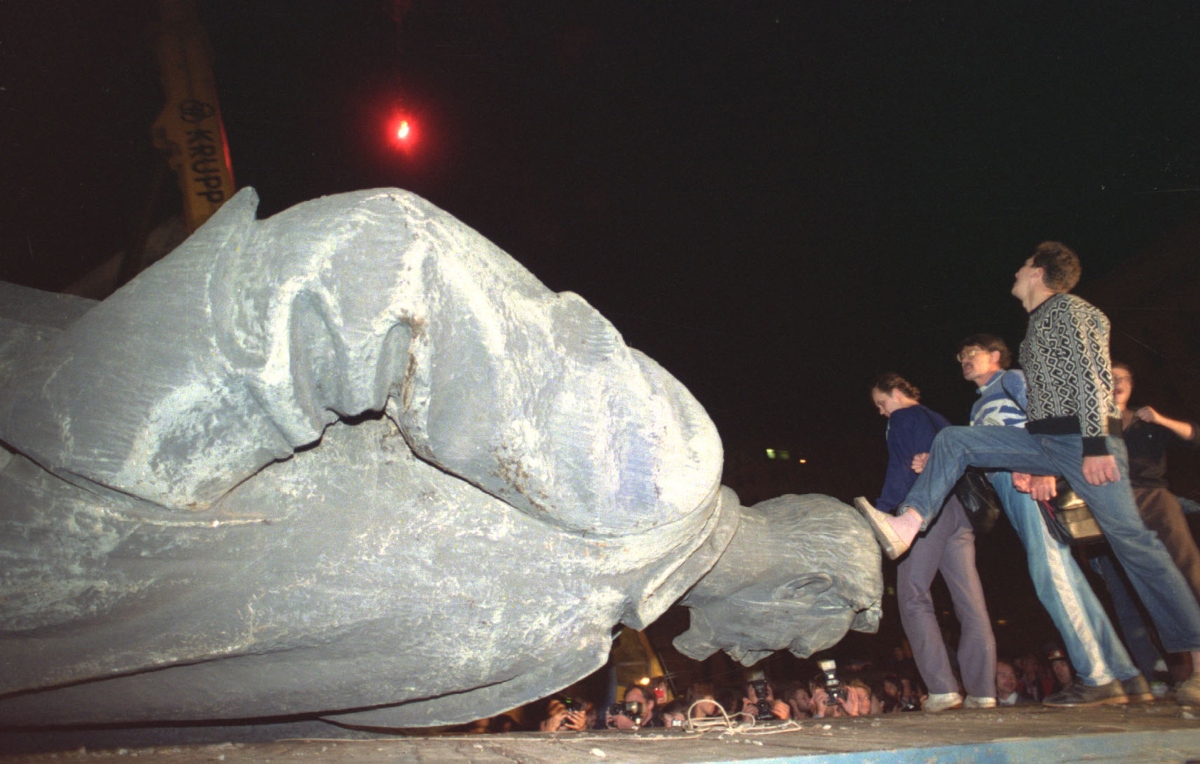

- The statue was torn down by protestors in August 1991 during the Soviet Union’s final months and photographs of Dzerzhinsky dangling from a crane became one of the defining images of the era. Later, the statue was installed outside a Moscow museum with dozens of other Communist memorials. Its place on Lubyanka Square has remained empty ever since.

- Over the past three decades there have been repeated calls to put Dzerzhinsky back. At first, this was a rallying cry for Communists, but now these appeals come just as often from the Russian right, which combines a belief in Orthodoxy, authoritarianism and imperialism with intense Soviet nostalgia. Inevitably, Dzerzhinsky’s return is opposed by the liberal intelligentsia. For the Kremlin, this question — like that of removing Lenin from his mausoleum — is an easy way to fire up debate and distract public opinion from more delicate political issues.

- City Hall launched its online poll on the statue this week. It offered residents of the capital two options: bring back Dzerzhinsky, or put up a new monument to Alexander Nevsky, a 13th warrior prince who defeated an army led by Teutonic Knights at the famous ‘Battle on the Ice’. Both figures are likely acceptable to President Vladimir Putin. Nevsky was seen in Tsarist times as the ruler who saved Russia from Catholicism and, under Stalin, he was held up as a Russian leader who resisted Western expansionism. Stalin effectively commissioned the famous 1938 movie about Nevsky directed by Sergei Eisenstein with a soundtrack composed by Sergei Prokofiev. A monument to Alexander Nevsky would also likely please the Russian Orthodox Church, which canonized Nevsky as long ago as the 16th century.

- Nevsky was reportedly the Kremlin’s preferred choice and a source told the BBC Russian Service on Sunday that the poll was rigged in the medieval prince’s favor. The same source suggested the whole discussion was designed to divert attention from Navalny, an explanation that was later repeated by media outlet Meduza. Either way, it seemed certain Lubyanka Square was about to acquire a statue. “Nobody wants to leave a hole there. The option ‘just leave it well alone’ is already off the table,” the influential editor-in-chief of Ekho Moskvy Alexei Venediktov stated. By Friday, Nevsky was ahead with 55 percent of the vote, against 45 percent for Dzerzhinsky.

- Then everything changed. Sobyanin unexpectedly announced Friday evening that there would be no new monument. “It’s obvious that public opinion is divided,” he wrote on his blog. “The vote itself is contributing to further conflict between people who hold differing views… the monuments that stand in our streets and squares should unite the public, not divide us.”

- A City Hall source told Open Media the decision to stop the poll came from the same place as the proposal to have it in the first place – the Kremlin. Perhaps someone realized that, far from being a distraction, the debate was actually inflaming passions. A second source said the level of support for Dzerzhinsky was far higher than the authorities expected.

Why the world should care

It’s difficult to say for sure who came up with the idea for this vote, or who scrapped it. However, it’s clear the original plan went awry. It seems unlikely it was a negative public reaction that influenced the authorities — three years ago, nobody was bothered by protests against the installation of another ugly statue of a medieval Russian prince in downtown Moscow. But it’s possible the authorities were worried about offending the FSB if Dzerzhinsky was snubbed. Either way, these sorts of public discussions about monuments are much more complicated than they once were. While they were once a convenient way for the Kremlin to manipulate public opinion, this is no longer the case.

Russia’s homegrown ‘dollar store’ chain set for giant IPO

Falling salaries and stalling economic growth have helped a new leader emerge in the Russian retail market: dollar store chain Fix Price. Due to float on the London Stock Exchange next month in an IPO, Fix Price was this week valued at up to $11.5 billion — making it Russia’s biggest retailer.

- Fix Price is currently holding a road show for its IPO and the organizers – Bank of America, J.P. Morgan and Russia’s VTB Capital – value the company between $7 and $11.5 billion. If all goes to plan, Fix Price will net $1.5 billion for development and pull off the biggest Russian IPO since 2017.

- Founders Sergei Lomakin and Artyom Khachaturyan set up the chain in 2007, opting to mimic the U.S. ‘dollar store’ format (at the time this meant everything went for 30 rubles). The format was partly a result of limited options resulting from the non-compete agreement Lomakin and Khachaturyan signed in the sale of their previous business, the Kopeika discount food stores.

- In its first few years, Fix Price saw turnover double each year. But that rate of growth looked destined to slow — until Russian salaries began to drop in 2014, boosting the budget store sector. Since 2017, Fix Price has seen its turnover and profits increase by at least 30 percent each year, more than twice as fast as the biggest Russian retailers.

- Such growth and profitability mean Fix Price could become Russia’s highest-valued retailer. Although market leaders X5 Retail Group and Magnit enjoy revenues over 10 times bigger than Fix Price’s annual $2 billion, their market values are just $9 billion and $7 billion, respectively.

- Salaries in Russia have every year for six of the last seven years. Since 2013, they have dropped by 10.3 percent. As a result, Russian retailers are trying to cash in on a demand for low-cost stores: X5 and Magnit launched new discounters in 2020, while the Svetofor chain, which slashes overheads by selling from warehouses with goods in boxes, last year became a top ten retailer.

Why the world should care

It’s unlikely Russian salaries will reverse their downward trend anytime soon, meaning that the fastest growing businesses will increasingly be those that help customers make savings.

As traditional offshore havens squeezed, Russian money finds new ways

Amid an intensified fight against global money laundering, many familiar routes for Russians to move funds overseas have been blocked. But people continue to find new ways of getting their capital out of Russia. This week The Bell kicks off a new series entitled “Where is Russian money going now?” looking at how financial flows abroad have changed in recent years. In the first article, we looked at some of the destinations that have replaced Cyprus and Latvia.

- Two major developments affected pathways to funnel Russian billions offshore: the international struggle against cross-border money laundering, and Putin’s desire to see capital return to Russia. First, at the request of U.S. regulators, the main gateways to Europe for Russian money — Cyprus and Latvia — toughened regulations for Russians. Then, Putin shut down the Cypriot route completely by tearing up tax agreements.

- At the same time, global regulators have been forcing offshore tax havens, such as the Cayman Islands and the British Virgin Islands, to disclose more information about company beneficiaries. And in 2018, Russia signed up to an international agreement that automatically shares tax information, giving the Russian authorities data on the finances of Russians in most major jurisdictions (except for the U.S. and the United Kingdom).

- But when there is a need, finance finds a way. One of the new gateways for departing Russian funds is the United Arab Emirates.

- A well-known Russian financial consultant described the UAE as a place through which money that is “grey, but not completely black” can pass. In other words, if funds are not associated with direct criminal activity, they are welcome. Several financiers described UAE at the ‘New Cyprus’: tax rates are zero, compliance is lenient and no tax information is handed to Russia. Most importantly, it’s easy to get residency and, once you’ve done that, it’s no problem to transfer money to European banks. Opening a company in the UAE, which grants you the right to apply for residency, costs about $10,000.

- There are other locations, although these can only handle relatively small sums of up to about $1.5 million. Thailand is becoming popular, according to two financial consultants, because compliance is not particularly onerous and there is no tax exchange with Russia. However, the Thai banking sector is under-developed and there is apparently a lack of investment tools.

- In the most difficult situations, or when the money is entirely ‘black’, it is sent to Georgia, Armenia or Kazakhstan in the hope it can then be moved further afield, one consultant explained.

Why the world should care

A desire to halt the flow of Russian funds offshore is something shared by many Western governments and the Kremlin. Together, they have made the process much more difficult, but it has not stopped.