Corporate raiding scandal engulfs Russian internet pioneer

Hello! This week our main story is about a corporate raiding scandal that has broken out between a Russian internet pioneer and, allegedly, a billionaire arts patron. We also look at Putin’s recent meetings with the Ukrainian and Belarusian leaders, how ex-Moscow Mayor Yuri Luzhkov will be remembered after his death this week, the cost of the new doping-linked ban on Russian sporting teams competing internationally, and we have the highlights of an interview with opposition leader Alexei Navalny.

Corporate raiding scandal engulfs Russian internet pioneer

Despite statements from President Vladimir Putin that business disagreements shouldn’t be solved via the courts, the end of 2019 has been marked by a major corporate scandal bearing the trademark of the Russia’s powerful security services. On one side is Igor Sysoev, the founder of the world’s most popular web server, Nginx, which was bought by U.S. investors this year for $670 million. On the other side, it would appear, is billionaire Alexander Mamut who is seeking to gain the rights to Nginx.

- What happened? Nginx’s Russian office and the apartments of its founders were searched Thursday, and founders Maksim Konovalov and Igor Sysoev were taken into custody. The two men spent the entire day being questioned by police, and were only released late at night.

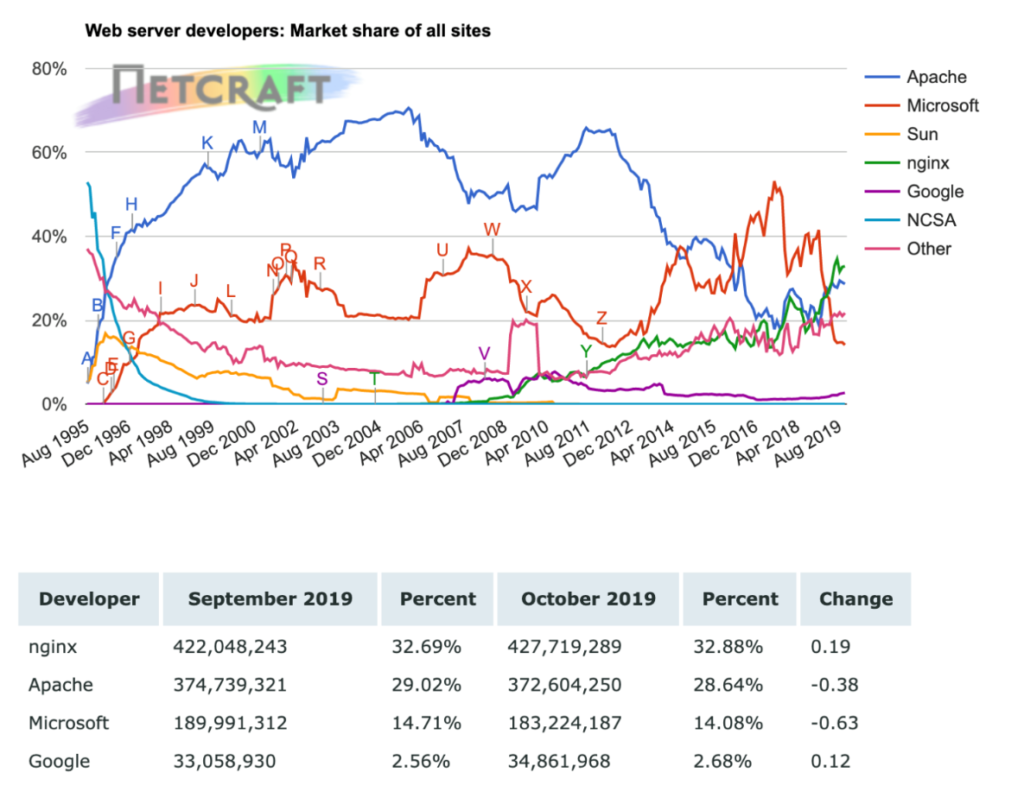

- What is the company? Founded in 2011, Nginx is now the world’s most popular web server — about a third of all websites use it. The company’s clients include Netflix, Dropbox, Adobe (Photoshop), and Buzzfeed. This year, U.S. company F5 Networks bought Nginx for $670 million. It was this deal which one of the founders of Nginx believes led to yesterday’s attack.

- What is the conflict? Sysoev developed Nginx while working at Russian web portal Rambler, which began to use the service. Rambler believes that it owns the rights to Nginx. Sysoev denis there was a link between the two (this was confirmed by former Rambler colleagues and lawyers who spoke to The Bell), and that he joined Rambler when the project was already at the final stages. There is nothing to directly link Rambler to recent events but media reports have suggested Rambler co-owner Mamut is behind the charges.

- What is Rambler? It is one of the pioneers of the Russian internet. During the early 2000s, Russia’s top media sites emerged on the basis of Rambler, though many were then taken over by the state or lost their funding. Between 1999 and 2005, when the company went public on the London Stock Exchange, its primary shareholder changed three times. In 2006, a major stake was bought by billionaire Vladimir Potanin and, in 2013, he merged it with one of Mamut’s projects. Until recently, Mamut was Rambler’s sole shareholder. Then, this summer, Sberbank bought 46.5 percent (the bank said was not part of the conflict).

- Who is Mamut? In the 1990s, Mamut became a member of then-President Boris Yeltsin’s inner circle, allegedly acting as a sort of private banker for Yeltsin and his family. But in the mid-2000s, Mamut began to change his image: he opened a fashionable architectural school called Strelka, and invited star architects to teach there. Mamut owns several cinemas and sponsors cultural events, trying to present himself as a sort of patron of the arts.

Alexander Mamut

Why the world should care: Every investment forum in Russia is accompanied by calls to keep businessmen out of jail and huge amount of money is spent on trying to improve the investment climate. But cases like Nginx, pressure on internet giant Yandex, or the arrest of investor Michael Calvey reveal the real story.

Putin leaves empty-handed after big meetings with Ukraine and Belarus

This week, Putin met the leaders of two of Russia’s neighbours: Belarus and Ukraine. Both meetings lasted late into the evening, but neither produced a breakthrough. The aims were very different: with Ukraine, Putin was negotiating an end to fighting, while he wanted to convince Belarus of the need for greater political integration. If you believe public statements, neither goal was achieved.

Ukraine. Putin met with Ukrainian President Volodymyr Zelensky on Monday for the first time as part of the so-called Normandy Format, which also includes France and Germany.

- The main takeaway was that the negotiations took place. There were few concrete steps forward. “For now, nothing,” was how Zelensky described the meeting. It was agreed there would be a prisoner exchange by the end of the year (but Zelensky and Putin may have different views of who should be swapped), and that the two leaders would meet again in four months time.

- The so-called ‘gas question’ was another topic of discussion — but it remained unresolved. The main issue is that state-owned Gazprom lost a $2.5 billion lawsuit it filed against Ukraine’s state-owned Naftogaz in a Stockholm arbitration court. Moscow is offering to pay the debt in gas rather than cash. Apparently, Kyiv is not opposed to such an arrangement, but the terms have not been agreed. A contract for 2020 has not yet been signed, meaning that no agreement is reached soon, there could be disruption to gas supplies via Ukraine.

Belarus. Many assumed that Putin’s meeting Saturday with Belarusian President Alexander Lukashenko would see agreement on the integration of Russia and Belarus. This topic has been under discussion for 20 years, but it has recently become more important: according to Bloomberg, one way for Putin to retain power after his current presidential term ends would be to become the leader of a new union state with Belarus.

- Putin denies he is seeking a total merger of the two countries, but he does talk of closer economic cooperation, particularly tax and currency policy. What this would mean in reality remains unclear. Lukashenko does not like the question being framed in this way, and he has said has said he does not want Belarus to lose its right to independent decision making.

- Russia can exert immense pressure on Belarus: the country’s economy is almost totally dependent on its larger neighbor. Roughly 50 percent of Belarus’ imports and exports are with Russia, and one of the Belarusian state’s primary sources of income is the sale of oil products (Belaurs is among the top 30 global exporters).

- Belarus produces very little crude oil: most of its imports come from Russia at a 50 percent discount to international prices. Due to changes in Russian tax legislation, however, the price at which Moscow sells to Minsk will rise to international levels by 2024. And this means a big hit to the Belarusian state coffers. Belarus has also not yet set the price of natural gas it imports from Russia for 2020. Putin and Lukashenko will meet again 20 December.

- A discount on natural gas is by no means the only carrot Russia can offer to Belarus. Direct investments in Belarus from Russia totalled $8 billion over the past decade, and Belarus has debt of $7.5 billion to Russia.

- Economists who spoke to The Bell agreed that integration is a political project. In theory, the integration would increase the size of the market for producers. But Belarus is so small in comparison with Russia (the country’s GDP is about the same as Moscow or St. Petersburg) that it would just be like adding another region — and a subsidized region at that.

Why the world should care: Belarus is one of Russia’s most loyal allies — in sharp contrast to Ukraine. But Lukashenko understands this perfectly never misses an opportunity to bring it up: this is the Belarusian counterweight to Russia’s economic leverage. From the meetings this week, it’s clear that talks with both countries will be long and excruciating.

What will former Moscow Mayor Luzhkov be remembered for?

Yuri Luzhkov died Tuesday at the age of 84. He was the mayor of the Russian capital city for 18 years and much of the city’s current appearance can be attributed to him. Luzhkov had a reputation as a capable manager without clearly defined political views — but with political ambitions.

- Born in Moscow, Luzhkov for three decades worked in the management of the Soviet Union’s chemical industry. He joined the Moscow city government in the 1980s on the orders of future president Boris Yeltsin, then head of the Moscow city committee of the Communist Party.

- Luzhkov became the mayor of Moscow in June 1992 and held the post until 2010 — he was elected three times and was once appointed mayor by Putin.

- During his time in charge, Luzhkov operated a populistic economic model whereby tax revenue from major companies was redistributed in the form of subsidies. This helped Luzhkov to achieve impressive results at the ballot box. But by the late 2000s, the city’s revenues were falling shrinking. Even so, some of Moscow’s most important roads, the MKhAD and the Third Ring, were completed under Luzhkov.

- In 1999, Luzhkov, together with ex-prime minister Yevgeny Primakov, created a political party in opposition to the Kremlin: Fatherland-All Russia. The plan was for Luzhkov to become prime minister, while Primakov would be president. However, the party lost the Duma elections and, then, merged with the Unity Party, which was later rebranded into today’s pro-Kremlin party, United Russia. Among the reasons for Fatherland-All Russia’s lack of success a negative media campaign and political mistakes: some believe Luzhkov would have had a better chance of becoming president than Primakov. After his defeat, Luzhkov accepted the failure and never expressed any further national political ambitions.

- While Luzhkov was ruling Moscow, his wife, Elena Baturina, built a huge construction business. She has topped (Rus) the Forbes list of Russia’s richest women for the last seven years in a row.

- The mayor’s career ended in 2010 after a falling-out with then-President Dmitry Medvedev. The reason for the firing was said to be Luzhkov’s attempts to play upon differences of opinion between the president and the prime minister (Putin), as well as scandals involving Baturina. It’s likely the final straw was a conflict over a highway through the Khimki Forest on the edge of Moscow: Medvedev was against the project, while Luzhkov supported it.

- Luzhkov accepted his firing as calmly as he handled his earlier defeat with Fatherland-All Russia. He moved to Austria, where he and his billionaire wife owned a 5-star hotel, Grand Tirolia, and then to London. Latterly he ran a farm in the Western exclave of Kaliningrad.

Why the world should care: Luzhkov is often compared to Moscow’s current mayor, Sergei Sobyanin. While Luzhkov was emotional, Sobyanin is reserved in public. Luzhkov’s Moscow was a fiefdom of chaotic parking, erratic development and tacky architecture, while Sobyanin’s Moscow is more sterile and ‘hipsterized’, filled with parks and markets that don’t build local communities. But these are differences not just between two mayors, but also between the 1990s and the 2010s.

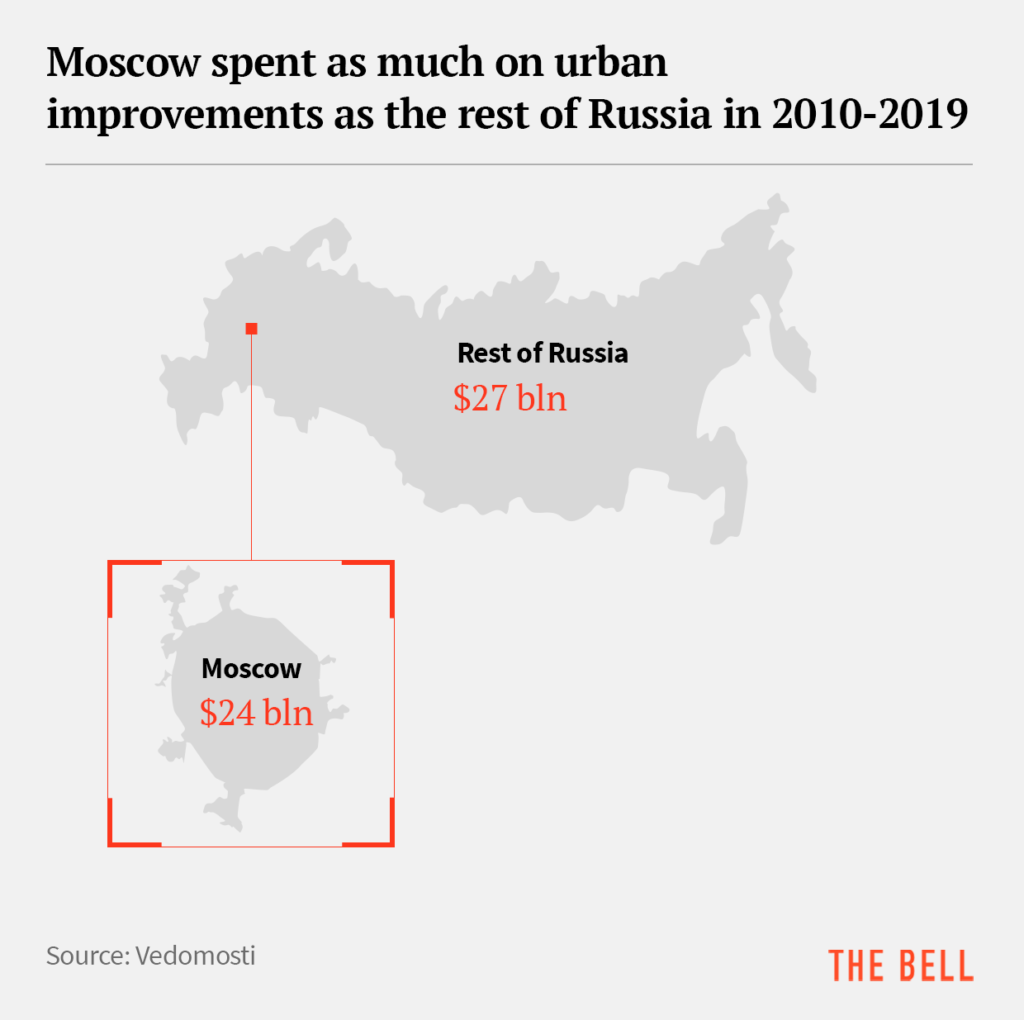

Extra: Statistics illustrate even more clearly the difference between the two officials. Under Luzhkov, 5 percent of Moscow’s budget was spent on urban improvements, while Sobyanin has pushed this up to 15 percent. In contrast, the percentage of the budget spent on pension subsidies over the same time period fell from 8 percent to 5.4 percent. The logic is simple: investments in sidewalks and parks are visible, while no-one can see pension subsidies.

The cost of Russia’s ban from international sport

This week, the World Anti-Doping Agency (WADA) imposed a four-year ban on Russia taking part in global sport. According to WADA, samples in the database of a Moscow anti-doping laboratory were deliberately switched earlier this year.

- Russian athletes have been banned from competing under the Russian flag in the Olympics and world championship events. “Clean” athletes will be able to compete under a neutral flag, just as they did during the 2018 Olympics.

- How much money has been wasted? The state funds about 60 percent of preparation for international events; the remaining 40 percent comes from private sponsors. In total, the state spends — on average — almost $400 million a year funding high profile sports.

- Approximately $16 million of government funds have already been spent on preparing Olympic teams, many of which will not be allowed to compete in the 2020 summer games in Tokyo or the 2022 winter games in Peking. And major private donors to popular sports are unlikely to be happy: they include billionaires Alisher Usmanov (who sponsors fencing) and Vladimir Lisin (who sponsors shooting). For example, Usmanov’s fund gives the Russian Olympic Committee about $9.5 million every year.

Why the world should care. Huge spending on the Olympics and the soccer World Cup have been justified, in part, by the necessity of raising Russia’s profile on the world stage. Now it would seem that not only were some of those funds spent in vain — but it is extremely difficult to talk about the sporting prestige of a country which has falsified doping results on multiple occasions.

‘Small business in Russia is not business but a way for people to survive’. Highlights from an interview with Navalny.

Russia’s leading opposition politician, Alexei Navalny, gave a long interview to The Bell founder, Elizaveta Osetinskaya. In the interview, he discusses the economy and business – not much is known about his views on these topics. The entire interview can be seen here in Russian, but we have translated some of the best quotes.

On relations with the West: “I don’t think we need to prove anything to anyone or do particularly good things for the West. We must do good things for ourselves. It is time to live well and wonderfully, to forget about Ukraine and everyone else. We have a unique situation in which we don’t have to go to war with anyone, and we can trade with everyone and make good money. And when we stop harming and actually do something real… we will finally become rich and become a more profitable trading partner, then everyone will love us and respect us.”

On what slows the Russian economy down. “Russia has a terrible judicial system. What sanctions? Sanctions are nonsense. They are our tenth-line problem. Our economy stopped growing in 2013 when there weren’t any sanctions, nor protests, and oil was at $120 a barrel.”

On taxes: “The tax burden on salaries in Russia is such that you can’t pay salaries on the books [deductions on payroll payments amount to about a 30 percent effective tax rate – The Bell]. You have to use these hellishly-complicated schemes, endlessly turn money into cash, to pay people their salaries off the books. In relation to small business, it’s important to mention the regulations. Because right now in Russia-2019, small business is not business but a way for people to survive.”

On unions. “A base-case scenario is that we should create a normal political system for business, a normal judicial system, and do away with excessive government regulation. Business will grow as a result of these changes. In parallel with this, we should offer people the opportunity to form professional unions, establish a minimum wage, and all those other things which are successfully used in capitalist countries.”

On why business is scared of Navalny: “The main point is is a principle of change. How they [business people] see it is that at the moment there are risks like they could take everything away from us, income levels are falling, investments are not arriving — but we are still somehow getting along. Things could change for the better, or for the worse. Therefore, just in case, it’s better to leave everything how it is.”